More Information

Submitted: December 05, 2025 | Accepted: December 16, 2025 | Published: December 17, 2025

Citation: Pino AJ, Chanco EC, Mariano MT. Comparative Evaluation of DECAF and BAP-65 Scores in Predicting Outcomes of COPD Exacerbations in In-patients at Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center. J Pulmonol Respir Res. 2025; 9(2): 059-069. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jprr.1001074

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jprr.1001074

Copyright license: © 2025 Pino AJ, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: COPD exacerbation; DECAF score; BAP-65 score; Mortality prediction; Mechanical ventilation

Comparative Evaluation of DECAF and BAP-65 Scores in Predicting Outcomes of COPD Exacerbations in In-patients at Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center

Allanys Joy Q Pino*, Edgardo C Chanco and Sol Mara T Mariano

B. Rodriguez StCebu City, 6000 Cebu, Philippines

*Corresponding author: Allanys Joy Q Pino, RMT, MD, Medical Officer III, B. Rodriguez StCebu City, 6000 Cebu, Philippines, Email: [email protected]

Objective: To compare the predictive performance of the Dyspnea–Eosinopenia–Consolidation–Acidemia–Atrial Fibrillation (DECAF) score and the Blood urea nitrogen–Altered mental status–Pulse–Age ≥65 years (BAP-65) score for in-hospital mortality and need for mechanical ventilation among Filipino patients hospitalized with AECOPD.

Methods: In this prospective cohort study, 80 adults admitted with AECOPD were consecutively enrolled. DECAF and BAP-65 scores were calculated within 24 hours of admission. Outcomes included in-hospital mortality and requirement for invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation. Diagnostic performance was assessed using sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC).

Results: In-hospital mortality occurred in 39 patients (48.8%). For mortality prediction, DECAF demonstrated significantly higher sensitivity than BAP-65 (97.4% vs. 69.2%) but lower specificity (26.8% vs. 61.0%). For prediction of mechanical ventilation, DECAF showed superior sensitivity (95.7%) and specificity (90.0%) compared with BAP-65 (58.6% and 80.0%, respectively). The high sensitivity of DECAF translated into a high negative predictive value for mortality (91.7%), whereas BAP-65 provided better discrimination of low-risk survivors. These results suggest DECAF is more effective in identifying high-risk patients requiring intensive care, while BAP-65 may be useful for rapid bedside risk assessment where resources are limited.

Conclusion: Both DECAF and BAP-65 scores are clinically useful for risk stratification in hospitalized AECOPD. DECAF is highly sensitive for identifying patients at risk of death or respiratory failure, while BAP-65 offers better specificity and simplicity. Their complementary use may optimize clinical decision-making, particularly in resource-limited settings.

Background of the study

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a leading global cause of illness and death, ranking as the third leading cause of mortality and the seventh leading cause of poor health worldwide [1,2]. The burden of disease is disproportionately borne by low- and middle-income countries, where access to preventive and specialized care remains limited [3]. It is estimated that 328 million people globally are affected, with 65 million suffering from moderate to severe forms [4,5].

The growing burden is attributed to increased tobacco use and population aging. From 2007 to 2017, the prevalence of COPD rose by 15.6% [6]. Risk factors associated with higher mortality include age, lung function, dyspnea severity, comorbidities, BMI, exercise capacity, arterial oxygen levels, C-reactive protein (CRP), and the BODE index [7].

An Acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD) is a sudden worsening of respiratory symptoms such as breathlessness, cough, and sputum production that often results in hospitalization. AECOPD events are linked to worsening lung function, reduced exercise capacity, increased healthcare costs, and a higher risk of death [8]. Prognostication during such exacerbations remains difficult, although several clinical tools have been developed to assist physicians [9]. Among these are the DECAF (Dyspnea, Eosinopenia, Consolidation, Acidemia, Atrial Fibrillation) and BAP-65 (Blood Urea Nitrogen, Altered Mental Status, Pulse ≥109, Age ≥65) scores. Both have been validated in predicting in-hospital mortality and other outcomes in AECOPD [9]. DECAF focuses on disease-specific parameters, while BAP-65 is simpler and more generalizable across various settings.

Although both tools are widely studied, comparative data remain limited, especially in low-resource settings like the Philippines. Most existing studies were conducted in Western populations, where healthcare infrastructure and patient demographics differ significantly. Additionally, neither scoring system is routinely used in COPD management at Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center (VSMMC), highlighting the need for localized evidence to guide clinical practice.

Significance of the study

This study aims to provide evidence-based guidance for improving risk stratification in Filipino patients admitted with AECOPD. Accurate predictions of in-hospital mortality and need for mechanical ventilation can improve clinical decision-making, facilitate patient and family discussions, and optimize resource use. By comparing the DECAF and BAP-65 scores within the local context, this research addresses a key knowledge gap. Both scores use routinely available data and are potentially suitable for use in resource-constrained hospitals. Determining which score performs better or whether a combination of both enhances prediction can help physicians prioritize high-risk patients for closer monitoring or early intervention. Moreover, the findings may inform institutional protocols, contribute to national COPD management strategies, and stimulate further research tailored to Filipino and Southeast Asian populations.

Several international studies have evaluated the performance of DECAF and BAP-65, with DECAF often showing slightly better mortality prediction [9]. However, limited research directly compares the two tools in Southeast Asian or Filipino cohorts. Local differences in disease severity, healthcare access, and comorbidities may influence the performance of these scores.

This study seeks to fill that regional evidence gap, validate the tools in a Filipino population, and support their potential inclusion in standard hospital protocols at VSMMC and beyond. The pragmatic nature of both tools also makes them ideal candidates for widespread use in resource-limited settings.

Research question

In hospitalized patients with acute exacerbation of COPD at Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center, how does the predictive accuracy of the DECAF score compare to the BAP-65 score in forecasting clinical outcomes, including in-hospital mortality, and need for mechanical ventilation?

General objective

To compare the predictive accuracy of the DECAF and BAP-65 scoring systems in forecasting clinical outcomes among hospitalized patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) at Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center.

Specific objectives

- To determine the accuracy of the DECAF score in predicting in-hospital mortality among AECOPD patients.

- To determine the accuracy of the BAP-65 score in predicting in-hospital mortality among AECOPD patients.

- To evaluate the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of DECAF and BAP-65 scores in predicting the need for mechanical ventilation during hospitalization.

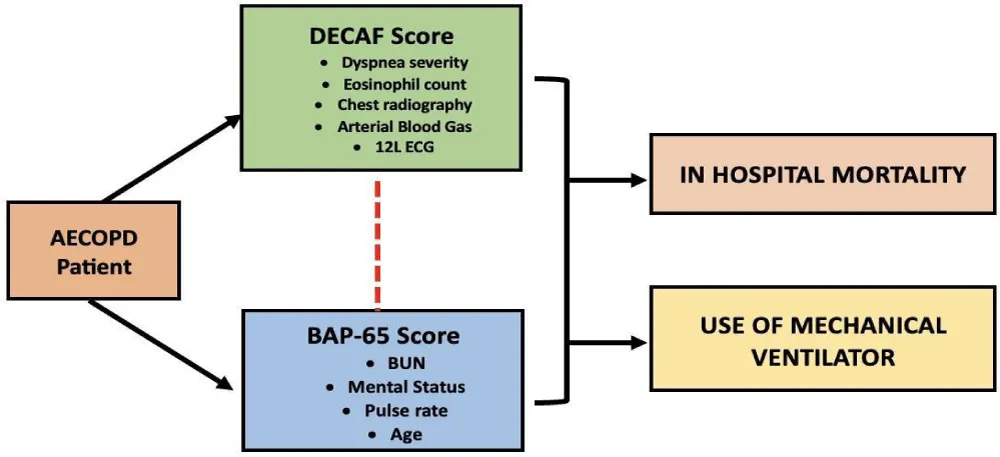

- To statistically compare the overall predictive performance (using AUC-ROC curves) of the DECAF and BAP-65 scores in forecasting adverse clinical outcomes (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Conceptual framework illustrating the relationship between admission clinical variables, DECAF and BAP-65 scores, and clinical outcomes (in-hospital mortality and mechanical ventilation requirement).

Study design

This study utilized a prospective cohort design to assess and compare the prognostic accuracy of the DECAF and BAP-65 scores in predicting clinical outcomes among patients hospitalized with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD). Data were collected at baseline (upon admission), and patients were then followed throughout their hospital stay until discharge or in-hospital death. This allowed for temporal observation between exposure (initial risk scores) and outcomes (mortality, need for mechanical ventilation).

The study was conducted over 6 months, from March 2025 to August 2025, allowing sufficient time to prospectively enroll patients and observe outcomes. The observation window for each patient extended from admission to discharge or death, without follow-up after discharge.

Study setting

The study was conducted at Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center (VSMMC), a government-owned tertiary medical center located in Cebu City, Philippines. VSMMC is a major teaching and training hospital under the Philippine government, providing comprehensive healthcare services that are accessible and affordable across diverse patient populations, regardless of social status. It has an extensive range of specialty and sub-specialty clinical departments, including internal medicine, pulmonary care, emergency medicine, and critical care services, making it well-equipped to manage acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD).

With a capacity that has progressively expanded over the years from its establishment in 1913, VSMMC currently accommodates up to 1,200 beds, serving a large and varied patient population, including referrals from different parts of the Central Visayas region. The hospital’s dedicated facilities and expertise in respiratory and internal medicine provide an ideal environment for conducting clinical research on COPD exacerbations and related outcomes among hospitalized patients.

The hospital’s infrastructure supports real-time laboratory testing, arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis, and radiography, enabling calculation of both DECAF and BAP-65 scores. Data collection was carried out in the emergency room, medical wards, and respiratory units, where patients with AECOPD are routinely admitted.

Study population and sampling technique

The study population consisted of adult patients admitted to Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center with a primary diagnosis of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD). These patients were hospitalized in medical wards or respiratory units during the study period. The population reflects patients who required inpatient care due to a worsening of their COPD symptoms, necessitating clinical and laboratory evaluation for both scoring systems (DECAF and BAP-65) and prospective monitoring of clinical outcomes such as mortality and need for mechanical ventilation. Patients were enrolled consecutively as they were admitted during the study period, using a non-probability purposive sampling technique. A total of 80 patients were included in the final analysis, based on pre-specified eligibility criteria and sample size estimation.

Inclusion criteria

- Patients aged 40 years and above admitted with a confirmed clinical diagnosis of acute exacerbation of COPD.

- Clinical diagnosis of AECOPD based on Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines, defined as acute worsening of respiratory symptoms (increased dyspnea, sputum volume, or purulence) necessitating a change in regular medication or hospitalization. Availability of necessary clinical and laboratory data at admission to calculate both DECAF and BAP-65 scores.

- Documented history of COPD supported by prior spirometry (post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.70).

- Availability of required clinical, laboratory, and radiographic data at admission to calculate DECAF and BAP-65 scores.

Exclusion criteria

- Patients with alternative or coexisting primary pulmonary diagnoses such as asthma, bronchiectasis, interstitial lung disease, or pulmonary tuberculosis.

- Admission for conditions not primarily related to AECOPD, such as trauma, malignancy, or advanced cardiac failure.

- Patients who were intubated before hospital admission.

- Patients who were discharged against medical advice (DAMA) or were transferred out before outcomes could be assessed.

- Incomplete clinical records prevent score calculation.

Sample size computation

The sample size of 80 patients was derived using a diagnostic test evaluation formula to compare two areas under the curve (AUCs). Based on the literature, the expected AUC for the DECAF score was estimated at 0.82 and for BAP-65 at 0.70. Assuming a type I error rate of 0.05, a power of 80%, a correlation coefficient of 0.6 between scores, and a mortality event rate of approximately 15%, the minimum sample size required was 72. To account for potential attrition and incomplete data, the sample was increased to 80. The relatively small cohort is acknowledged as a limitation that may affect generalizability and precision of estimates. These calculations were performed using MedCalc software version 22.0. The estimated patient pool during the study period, based on VSMMC census data, was approximately 180 to 200 AECOPD admissions over six months.

Operational definitions of study variables

DECAF score: A clinical prognostic tool used to predict in-hospital mortality and severity in patients admitted with acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD). The score ranges from 0 to 6 and is calculated based on five components:

Dyspnea: Scored 1 for eMRCD 5a (too breathless to leave the house) and 2 for eMRCD 5b (too breathless to dress/wash).

Eosinopenia, defined as an eosinophil count less than 0.05 × 10^9/L (1 point)

Consolidation visible on chest radiograph (1 point)

Acidemia, indicated by arterial pH < 7.30 (1 point)

Presence of atrial fibrillation, including paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (1 point). Higher DECAF scores indicate a higher risk of mortality and worse prognosis during hospital admission.

Risk categories: Low (0–1), Intermediate (2), High (3–6)

BAP-65 score: A risk stratification score that predicts mortality and mechanical ventilation needs in AECOPD patients. The BAP-65 score comprises four components:

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level > 25 mg/dL (1 point)

Altered mental status (1 point)

Pulse rate > 109 beats per minute (1 point)

Age ≥ 65 years (1 point).

Scores range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating increased risk for adverse outcomes.

Risk categories: Low (0), Moderate (1–2), High (3–4)

In-hospital mortality: Death occurred during the hospitalization period for an acute exacerbation of COPD. This is recorded as a binary outcome (yes/no).

Mechanical ventilation requirement: The need for invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilatory support during the hospital stay for respiratory failure related to AECOPD. This is also documented as a binary outcome.

Acute Exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD): A clinical diagnosis based on the worsening of respiratory symptoms beyond normal day-to-day variations, requiring hospitalization and treatment escalation in a patient with established COPD.

The severity of COPD (GOLD stages) refers to the classification of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease based on the degree of airflow limitation measured by spirometry, combined with symptom burden and exacerbation risk. This classification system is established by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD).

Data collection procedure

Before the start of data collection, the research protocol was reviewed and approved by the VSMMC Research Ethics Committee. Data collection was conducted prospectively using standardized data collection forms. All clinical and laboratory information required for DECAF and BAP-65 score computation was obtained within the first 24 hours of admission. Trained Internal Medicine residents, supervised by the principal investigator, collected data through patient interviews, physical examinations, and review of electronic and paper-based medical records. Laboratory values were obtained from official hospital laboratory reports, and chest radiographs were interpreted by board-certified radiologists. Dyspnea and mental status were independently assessed in a subset of patients to determine inter-rater reliability using Cohen’s kappa.

Outcome data were collected prospectively throughout hospitalization. Patients were followed daily to monitor clinical progression, including whether mechanical ventilation was initiated and whether the patient survived to discharge. Outcome assessors were blinded to the initial DECAF and BAP-65 scores to reduce observer bias. Data were anonymized by assigning unique patient identifiers and were entered into a password-protected database accessible only to the research team.

Data processing and analysis

Data collected from patient records and clinical assessments were initially entered and organized using Microsoft Excel to ensure proper data management, cleaning, and preparation for statistical analysis. This included verification of data accuracy, coding of categorical variables, and handling of any missing values.

Final statistical analyses were performed using Jamovi software, a user-friendly open-source statistical package. Descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages were computed to summarize patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and outcome variables. Comparative analysis was done using the chi-square test. The predictive accuracy of the DECAF and BAP-65 scores was assessed by calculating sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and the areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUROCs) for outcomes including in-hospital mortality and need for mechanical ventilation using a web-based calculator, MedCalc. Statistical significance was set at a p -value < 0.05.

Scope and limitations of the study

This study focused on hospitalized adult patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) at Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center. It aimed to evaluate and compare the predictive accuracy of two clinical risk scoring systems—DECAF and BAP-65 in forecasting important clinical outcomes, such as in-hospital mortality and need for mechanical ventilation. Data collection included clinical, laboratory, and radiologic parameters necessary to calculate both scores, gathered at hospital admission and linked to prospectively observed outcomes during the inpatient stay. The study exclusively targeted patients admitted to medical wards and respiratory units, reflecting the real-world clinical context of COPD exacerbation management in a tertiary care hospital setting.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. The sample size of 80 patients, while providing valuable preliminary data, was relatively small, which may affect the statistical power and limit generalizability outside the study setting. The study was conducted in a single tertiary medical center, which may limit the applicability of results to other healthcare environments with different patient populations or resource availability. Additionally, the study design was observational and relied on routinely collected clinical data, leaving potential for missing data or measurement variability in score components.

Furthermore, the study did not include patients with significant comorbid respiratory diseases or those already on mechanical ventilation before admission, restricting the findings to a subset of COPD exacerbation patients. The scope was also limited to short-term inpatient outcomes without follow-up beyond hospitalization, so the long-term prognostic value of the DECAF and BAP-65 scores was not assessed. Lastly, the study did not investigate potential benefits of combining the two scores or incorporating additional biomarkers such as blood lactate, which emerging evidence suggests may enhance predictive accuracy.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in full adherence to the ethical standards and guidelines set forth by the Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center (VSMMC) Research Institute and its Research Ethics Committee (REC) with code of VSMMC-REC-I-2024-062. Before data collection, the study protocol was submitted for ethical review and approval by these bodies to ensure the protection of participant rights and welfare throughout the research process, with waiver of informed consent approved.

Confidentiality was maintained through the de-identification of data and secure storage. The study complied with the Philippines’ Data Privacy Act of 2012, safeguarding the confidentiality, security, and privacy of all patient data collected. Furthermore, it adhered to the National Ethical Guidelines for Health and Health-Related Research in the Philippines, which align with international standards for ethical conduct in health research. The principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, including respect for persons, beneficence, and justice, informed the study’s design and implementation to uphold human dignity and ensure ethical treatment of all research participants.

Lastly, this research was carried out in compliance with the residency requirements of Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center and the Philippine College of Physicians, fulfilling academic and professional standards for clinical research within the local healthcare education framework [10-20].

The study involving 80 patients admitted with acute exacerbation of COPD at Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center provides valuable insights into the clinical profile and outcomes of this population, as well as the potential utility of DECAF and BAP-65 scores in predicting prognosis.

Participants had a mean age of nearly 69 years, reflecting an older patient group typically affected by COPD. The predominance of males (77.5%) and smokers (97.5% with heavy smoking history averaging 32 pack-years) aligns with known COPD risk factors, emphasizing the role of tobacco exposure in disease burden. The average body mass index (BMI) of 21.15 kg/m^2 suggests that many patients might be underweight or at the lower end of normal, which is often associated with poorer COPD outcomes, as nutritional status influences respiratory muscle strength and immune function [21,22].

Frequent comorbidities were present, with hypertension in over half of the patients (63.7%), and notable proportions having congestive heart failure (22.5%) and prior myocardial infarction (12.5%). These cardiovascular conditions complicate COPD management and increase vulnerability to adverse outcomes, including exacerbations and mortality.

Vital signs on admission showed elevated respiratory rates (mean 33 breaths per minute) and heart rates (mean 101 beats per minute), indicative of respiratory distress and systemic stress. Blood pressure readings were within moderate ranges but reflect variability due to acute illness. Temperature was slightly elevated on average, consistent with inflammatory or infectious triggers for exacerbation.

Laboratory data revealed elevated blood urea nitrogen (mean 28.7 mg/dL) and creatinine (mean 1.40 mg/dL), suggesting impaired renal function possibly due to hypoxia, dehydration, or systemic illness. White blood cell counts were high (mean 15.2 ×10^9/L), pointing to inflammation or infection on admission. Low mean eosinophil count (0.962 ×10^9/L) could reflect eosinopenia, one of the DECAF score components linked to worse outcomes. Acid-base disturbance was evident with a mean pH of 7.24 (acidotic state), and elevated PCO2 (mean 77.9 mmHg) indicates hypercapnic respiratory failure, a critical complication of COPD exacerbations.

Clinically, a striking 87.5% of patients required mechanical ventilation at admission or during hospitalization, highlighting the severity of respiratory failure in this cohort. The median number of intubations was zero, but the range (0–3) shows that some patients required repeated ventilatory support. Similarly, the history of previous exacerbations and mechanical ventilation episodes (median 1, range 0-4) underlines the recurrent and severe nature of disease in these patients.

Despite more than half (51.2%) being successfully discharged, nearly half (48.8%) of the cohort succumbed during hospitalization. This high mortality rate emphasizes the critical condition of patients admitted with acute COPD exacerbations and the challenges in management.

Generally, these results portray an acutely ill, older, predominantly male, heavy-smoking patient population with significant comorbidities and respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. The substantial in-hospital mortality underlines the importance of reliable prognostic tools such as DECAF and BAP-65 scores to aid clinicians in early risk stratification, targeted management, and potentially improving outcomes by identifying those at highest risk. The detailed clinical and laboratory profiles collected provide a comprehensive baseline for evaluating and comparing the predictive capacities of these scoring systems in this high-risk population (Table 1) [23,24].

| Table 1: Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants (n = 80). | |

| Characteristic | n (%); Mean ± S.D./ Median (IQR) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 68.8 ± 11.1 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 62 (77.5) |

| Female | 18 (22.5) |

| Smoking History | |

| Smoker | 78 (97.5) |

| Pack years (mean ± SD) | 32.1 ± 22.9 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 21.15 ± 3.94 |

| Comorbidities (%) | |

| Hypertension | 51 (63.7) |

| Chronic Heart Failure | 18 (22.5) |

| Myocardial infarct | 10 (12.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7 (8.8) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 2 (2.5) |

| Renal | 3 (3.8) |

| Vital Signs | |

| SBP | 117 ± 17.3 |

| DBP | 75.2 ± 10.0 |

| RR | 33.1 ± 4.62 |

| HR | 101 ± 16.3 |

| Temperature | 37.4 ± 0.697 |

| Laboratory Parameters | |

| BUN | 28.7 ± 18.6 |

| Creatinine | 1.40 ± 0.990 |

| FBS | 100 ± 26.9 |

| Sodium | 138 ± 6.48 |

| WBC | 15.2 ± 7.10 |

| Eosinophils | 0.961 ± 1.44 |

| pH | 7.24 ± 0.0912 |

| PCO2 | 77.9 ± 19.4 |

| Need for Mechanical Ventilation (%) | 70 (87.5) |

| Number of times intubated | 0 (0 ~ 3) |

| Number of AECOPD | 1 (0 ~ 4) |

| History of Mechanical Ventilation | 1 (0 ~ 4) |

| In-hospital Mortality (%) | |

| Discharged | 41 (51.2) |

| Expired | 39 (48.8) |

The results indicate a significant association between both the DECAF and BAP-65 risk classifications and the clinical outcomes of patients hospitalized with COPD exacerbations, specifically regarding their survival or mortality during hospital stay. For the DECAF score, 30 out of 41 patients who were discharged (survivors) were still classified as high risk, while an even higher proportion—38 out of 39 patients who died—were also classified as high risk. The statistical significance (p = .002) indicates a strong correlation between a high DECAF score and mortality. This suggests that the DECAF score is effective in identifying patients at high risk of death; however, the fact that a substantial number of survivors were also classified as high risk might imply that while DECAF is sensitive in flagging critically ill patients, it may have limited specificity, potentially classifying some patients as high risk who ultimately survive [25].

For the BAP-65 score, the distribution shows that 25 of the 41 discharged patients were classified as low risk, and 27 of the 39 patients who died were classified as high risk. The significant p - value of .007 reinforces that higher BAP-65 scores correspond to worse outcomes. Compared to DECAF, the BAP-65 score shows a clearer distinction among survivors, with a majority in the low-risk category, which suggests it may have better specificity in identifying those less likely to die. However, almost equal proportions of patients who died were classified as high risk by BAP-65, reflecting the score’s utility in risk stratification.

Both scoring systems demonstrate statistically significant correlations with patient outcomes, validating their use in predicting mortality among hospitalized COPD exacerbation patients. The DECAF score tends to classify a larger portion of both survivors and non-survivors as high risk, indicating strong sensitivity but possibly lower specificity. This might be beneficial in clinical settings to ensure high-risk patients are closely monitored but may lead to overestimation of risk in some survivors. The BAP-65 score shows a more balanced risk distribution among survivors and non-survivors, suggesting better discrimination to identify patients who truly have a low risk of death [25,26].

These findings indicate that while both scores are useful tools for mortality prediction, they each have complementary strengths: DECAF may be preferred when maximizing sensitivity is critical, and BAP-65 may be better for ruling out high risk in some patients. Given the significant p - values for both scores, their combined or contextual use in clinical practice could enhance decision-making, triage, and targeted resource allocation in managing acute COPD exacerbations. Overall, the data support the clinical relevance of using DECAF and BAP-65 scores as prognostic tools, with each score offering unique predictive insights into patient outcomes during hospitalization for COPD exacerbations.

Further, the results reveal significant associations between the DECAF and BAP-65 risk classifications and the requirement for mechanical ventilation (MV) among patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of COPD.

For the DECAF score, 67 patients classified as high risk required mechanical ventilation, with a highly significant p - value (p < .001). This strong association indicates that the DECAF score effectively identifies patients at high risk who are likely to need ventilatory support during their hospital stay. The strong statistical significance reflects the score’s robust predictive capability regarding respiratory failure severity necessitating MV, underscoring its clinical value for early risk stratification and management planning.

Regarding the BAP-65 score, 8 patients classified as low risk did not require mechanical ventilation, while 41 out of 70 patients who required MV were classified as high risk. The significant p - value (p = .022) suggests that BAP-65 also has meaningful predictive power in distinguishing those who will need ventilatory support. However, compared to DECAF, BAP-65 identified a smaller number of high-risk patients who needed MV, which may indicate relatively lower sensitivity for this outcome.

The DECAF score demonstrates excellent sensitivity and strong predictive accuracy for identifying patients who require mechanical ventilation, making it a valuable clinical tool for anticipating and preparing for respiratory support needs in severe COPD exacerbations. The BAP-65 score, while also significantly associated with mechanical ventilation requirement, shows a more moderate predictive relationship. The proportion of low-risk patients who did not need MV suggests BAP-65 may have reasonable specificity to exclude those unlikely to require ventilation [23].

The difference in predictive strength between the DECAF and BAP-65 scores for mechanical ventilation need may stem from differences in score components: DECAF includes parameters like acidemia, consolidation on chest X-ray, and eosinopenia, which are directly related to severity of respiratory failure; BAP-65 relies on broader clinical and laboratory markers like blood urea nitrogen, altered mental status, pulse, and age.

Clinically, DECAF’s stronger association with MV requirement supports its use in guiding decisions about intensive care unit admission, ventilatory support readiness, and resource allocation. BAP-65 can still provide useful risk stratification but may be complemented by other clinical parameters or tools.

In practice, using both scores together may optimize early identification of patients at risk of respiratory failure while balancing sensitivity and specificity to improve tailored management plans. Generally, both DECAF and BAP-65 scores are useful predictors of mechanical ventilation requirement in hospitalized COPD exacerbations, with DECAF demonstrating superior predictive performance for this specific outcome. This highlights the importance of utilizing comprehensive and targeted scoring systems like DECAF in severe cases to enhance clinical decision-making and patient care (Table 2).

| Table 2: Distribution of DECAF and BAP-65 scores according to In-Hospital Mortality and Mechanical Ventilation Requirement. | ||||

| Score Category | In-hospital Mortality | Chi-square Statistic | p - value | |

| Discharged n = 41 | Expired n = 39 | |||

| DECAF Score | ||||

| Low risk (0-2) | 11 (26.8) | 1 (2.6) | X2(1) = 9.23 | .002a |

| High risk (>2) | 30 (73.2) | 38 (97.4) | ||

| BAP-65 Score | ||||

| Low risk (0-2) | 25 (61.0%) | 12 (30.8) | X2(1) = 7.34 | .007 |

| High risk (>2) | 16 (39.0) | 27 (69.2) | ||

| Need for Mech Vent | ||||

| No n = 10 | Yes n = 70 | |||

| DECAF Score | ||||

| Low risk (0-2) | 9 (90.0) | 3 (4.3) | X2(1) = 50.4 | <.001 |

| High risk (>2) | 1 (10.0) | 67 (95.7) | ||

| BAP-65 Score | ||||

| Low risk (0-2) | 8 (80.0) | 29 (41.4) | X2(1) = 5.24 | .022 |

| High risk (>2) | 2 (20.0) | 41 (58.6) | ||

The predictive performance of the DECAF and BAP-65 scores in forecasting in-hospital mortality among patients with acute exacerbation of COPD reveals distinct characteristics and clinical implications for each scoring system. The DECAF score demonstrates a markedly high sensitivity of 97.44%, indicating its strong ability to correctly identify nearly all patients who ultimately succumbed during hospitalization. This high sensitivity minimizes the likelihood of missing patients at risk of death, which is crucial for timely intervention and close monitoring. However, the DECAF score exhibits a comparatively low specificity of 26.83%, signifying a substantial rate of false-positive classifications, where many patients who survived were nonetheless categorized as high risk. The positive predictive value (PPV) of 55.88% suggests a moderate probability that patients identified as high risk actually experience mortality, while the high negative predictive value (NPV) of 91.67% reinforces the confidence in low-risk classifications corresponding to survival.

In contrast, the BAP-65 score presents a more balanced predictive profile with a sensitivity of 69.23% and a specificity of 60.98%. This signifies that while BAP-65 identifies a smaller proportion of patients who eventually died compared to DECAF, it more accurately distinguishes survivors from non-survivors, reducing the incidence of false positives. The PPV of 62.79% indicates that nearly two-thirds of those classified as high risk succumbed, comparable to the DECAF score, though its NPV of 67.57% is notably lower, reflecting less certainty when patients are categorized as low risk.

Comparatively, the DECAF score prioritizes sensitivity over specificity, making it a valuable tool in clinical settings where it is critical to detect all patients at risk of mortality to prevent missed diagnoses. However, its low specificity may lead to overestimation of risk among survivors and potentially unnecessary allocation of healthcare resources. Conversely, BAP-65’s more balanced sensitivity and specificity suggest it may be more suited for scenarios where avoiding overtreatment and optimizing resource use is a priority, albeit with the risk of under-identifying some high-risk patients.

In summary, the DECAF score’s superior sensitivity renders it more effective for identifying patients at risk of mortality, whereas the BAP-65 score offers improved specificity and may better exclude patients unlikely to die. The choice between these scoring systems should be informed by clinical objectives and resource considerations, with the possibility that a combined or contextualized approach may enhance risk stratification and patient management in acute COPD exacerbations (Table 3).

| Table 3: Predictive Performance of DECAF and BAP-65 scores for In-Hospital Mortality. | ||

| Statistic | DECAF Score | BAP-65 Score |

| Sensitivity (%) | 97.44 [86.53 – 99.94] | 69.23 [53.42 – 82.98] |

| Specificity (%) | 26.83 [12.44 – 42.94] | 60.98 [44.50 – 75.80] |

| Positive Predictive Value (%) | 55.88 [51.10 – 60.55] | 62.79 [52.18 – 72.30] |

| Negative Predictive Value (%) | 91.67 [59.83 – 98.78] | 67.57 [53.52 – 75.33] |

The predictive performance of the DECAF and BAP-65 scores in forecasting the need for mechanical ventilation among patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of COPD demonstrates notable differences in sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values that carry important clinical implications.

The DECAF score exhibits a very high sensitivity of 95.71%, indicating that it correctly identifies almost all patients who will require mechanical ventilation. This is complemented by a high specificity of 90%, reflecting strong ability to accurately classify those who do not need mechanical ventilation. The positive predictive value (PPV) of 98.53% further underscores the reliability of the DECAF score in predicting true cases requiring ventilatory support, while the negative predictive value (NPV) of 75.00% indicates a moderate level of confidence that patients classified as low risk will not require mechanical ventilation. Overall, these results reflect excellent discriminatory power of the DECAF score for determining respiratory failure necessitating mechanical ventilation.

Conversely, the BAP-65 score shows a more moderate sensitivity of 58.57%, signifying that it identifies just over half of the patients who eventually needed mechanical ventilation, and thus may miss a substantial number of high-risk patients. Its specificity of 80% indicates reasonable accuracy in ruling out patients who do not require ventilatory support. The PPV of 95.35% suggests that most patients classified as high risk do indeed require mechanical ventilation, though slightly less than DECAF. However, the very low NPV of 21.62% reveals limited ability of BAP-65 to confidently exclude patients from needing mechanical ventilation when classified as low risk.

Comparatively, the DECAF score outperforms BAP-65 across all key metrics in predicting mechanical ventilation requirement. Its high sensitivity and specificity demonstrate its robustness in both capturing patients at risk and minimizing false positives, essential for optimal resource allocation and patient care in critical settings. The superior PPV of DECAF assures clinicians that patients flagged as high risk will almost certainly need ventilatory support, while its moderate NPV provides reasonable confidence in identifying those unlikely to require it [25,26].

In contrast, BAP-65’s moderate sensitivity and specificity, combined with its low NPV, limit its utility as a standalone tool for mechanical ventilation prediction. While it performs well in confirming patients who do need ventilation (high PPV), it is less reliable in safely excluding those who do not, which could lead to under-preparedness in anticipating respiratory failure.

In summary, the DECAF score demonstrates superior overall performance in predicting the need for mechanical ventilation in acute COPD exacerbations, making it a more effective tool for guiding clinical decisions regarding respiratory support. The BAP-65 score, while useful in certain contexts, shows limitations particularly in sensitivity and negative predictive value, suggesting that it should be used cautiously or in conjunction with other clinical assessments when predicting mechanical ventilation requirements (Table 4).

| Table 4: Predictive Performance of DECAF and BAP-65 scores for Mechanical Ventilation Requirement. | ||

| Statistic | DECAF Score | BAP-65 Score |

| Sensitivity (%) | 95.71 [87.98 – 99.11] | 58.57 [46.17 – 70.23] |

| Specificity (%) | 90.00 [55.50 – 99.75] | 80.00 [44.39 – 97.48] |

| Positive Predictive Value (%) | 98.53 [91.25 – 99.77] | 95.35 [85.39 – 98.63] |

| Negative Predictive Value (%) | 75.00 [87.69 – 98.62] | 21.62 [15.39 -29.50] |

This study evaluated the predictive performance of the DECAF and BAP-65 scores for clinical outcomes among patients admitted with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) at Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center. Both scoring systems demonstrated significant prognostic value in predicting in-hospital mortality and the need for mechanical ventilation, with the DECAF score showing superior overall performance.

DECAF demonstrated a strong capacity to identify patients at risk of in-hospital death, ensuring that nearly all high-risk individuals were recognized early, which is vital for timely intervention in the acute care setting. This heightened sensitivity reflects the inclusion of clinical, laboratory, and radiologic parameters such as acidemia and chest radiograph consolidation, which are robust markers of disease severity. While sensitivity was excellent, the low specificity suggests that some patients classified as high risk survive, potentially leading to increased use of limited resources [27,28]. The BAP-65 score, however, exhibited a more balanced sensitivity and specificity, with moderate sensitivity but better specificity than DECAF. This balance is advantageous in prioritizing resource allocation by more accurately identifying patients less likely to experience adverse outcomes, although it risks missing some patients at risk of mortality.

For predicting the need for mechanical ventilation, DECAF again outperformed BAP-65, demonstrating both high sensitivity and specificity. This affirms DECAF’s usefulness in foreseeing respiratory failure severity, allowing for better planning of critical care resources. BAP-65’s comparatively low negative predictive value limits its reliability in ruling out patients who will require mechanical ventilation, cautioning against its exclusive use for this purpose.

The demographic and clinical profile of this cohort—elderly, predominantly male, with extensive smoking histories and frequent cardiovascular comorbidities—mirrors typical COPD patients but with a high burden of illness severity, as reflected by the nearly 50% in-hospital mortality and high ventilatory requirements [29-32]. These findings highlight the importance of reliable risk stratification tools adapted to local patient characteristics and healthcare capabilities.

Each scoring system presents inherent limitations. DECAF’s dependency on imaging and arterial blood gas analysis may restrict its applicability in resource-limited settings, whereas BAP-65’s simplicity enables rapid bedside assessment but at the expense of sensitivity. DECAF’s high sensitivity ensures early identification of patients at risk of death or respiratory failure, however, its low specificity indicates potential overestimation of risk, which may strain limited resources. Clinicians should consider these factors when choosing an appropriate tool, potentially employing both scores in complementary roles alongside comprehensive clinical assessment [23,25].

This study’s single-center design and relatively small sample size may limit generalizability, and future multi-center studies with larger populations and longer follow-up are warranted to validate these findings and explore the integration of novel biomarkers and technologies for enhanced risk prediction. Nonetheless, this locally based study provides valuable data supporting the clinical utility of DECAF and BAP-65 scores in Filipino patients with AECOPD.

Both DECAF and BAP-65 scores are valuable prognostic tools in hospitalized patients with acute exacerbations of COPD. The DECAF score demonstrated superior sensitivity and specificity in predicting in-hospital mortality and the need for mechanical ventilation, making it the preferred tool for comprehensive risk assessment in well-resourced clinical settings. The BAP-65 score offers a simpler alternative with a balanced predictive profile, suitable for rapid bedside evaluation, especially where diagnostic resources are limited. Optimizing patient care may involve integrating these scoring systems with clinical judgment, tailored to local healthcare resources and patient populations.

Recommendation

Based on the findings of this study and aligned with existing literature, it is recommended that the DECAF score be utilized as the primary prognostic tool for risk stratification among hospitalized patients with acute exacerbations of COPD, particularly in settings where comprehensive clinical, laboratory, and radiologic assessments are feasible. Its superior sensitivity and specificity for predicting mortality and the need for mechanical ventilation make it valuable in guiding clinical decisions and resource allocation.

However, the BAP-65 score remains a useful alternative, especially in resource-limited or emergency settings due to its simplicity and reliance on readily available clinical parameters. Its balanced predictive performance allows for quick and pragmatic risk assessment when access to extensive diagnostics is limited.

In clinical practice, integrating both scores with thorough patient evaluation and clinical judgment can optimize patient management. This ensures high-risk patients receive timely interventions through early ICU referral and ventilatory preparedness, intermediate risk patients for close monitoring and early escalation planning, while minimizing unnecessary treatment for low-risk individuals and applying standard therapy in the ward.

Further validation studies in diverse local populations and healthcare settings are encouraged to refine and standardize the use of these scoring systems. The single-center design and small sample size limit generalizability. Only short-term in-hospital outcomes were assessed. Future multicenter studies with larger cohorts, longer follow-up, and integration of emerging biomarkers are recommended.

The completion of this study would not have been possible without the invaluable support and contributions of many individuals and institutions.

First and foremost, I give praise and glory to God, the Father Almighty, my source of strength and inspiration, who made all things possible. Through His guidance and enlightenment, I was able to accomplish this research.

I extend my deepest gratitude to my co-authors, Dr. Edgardo Chanco and Dr. Sol Mariano, for their unwavering guidance, expertise, and encouragement throughout this journey. Their insights and mentorship have been instrumental in shaping and refining this study.

I am also sincerely grateful to the Vicente Sotto Memorial Medical Center, particularly the Department of Internal Medicine, for providing the resources and motivation that formed the foundation of this work. Special thanks are likewise due to the Research Institute and Ethics Review Board for their approval and steadfast support in ensuring that this study adhered to the highest ethical standards.

Finally, to my family and friends, thank you for your encouragement, patience, and understanding as I devoted my time and efforts to this endeavor. Your support has been my constant source of strength and perseverance.

- Viegi G, Pistelli F, Sherrill DL, Maio S, Baldacci S, Carrozzi L. Definition, epidemiology and natural history of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(5):993-1013. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00082507

- World Health Organization. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-(copd)

- Chen S, Kuhn M, Prettner K, Yu F, Yang T, Bärnighausen T, et al. The global economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for 204 countries and territories in 2020–2050: a health-augmented macroeconomic modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11(8). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00217-6

- World Health Organization. Burden of COPD [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2163-2196. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23245607/

- Safiri S, Carson-Chahhoud K, Noori M, Nejadghaderi SA, Sullman MJ, Ahmadian Heris J, et al. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ. 2022. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2021-069679

- Hoogendoorn M, Hoogenveen RT, Rutten-van Molken MP, Vestbo J, Feenstra TL. Case fatality of COPD exacerbations: a meta-analysis and statistical modelling approach. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(3):508-515. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00043710

- Kim V, Aaron SD. What is a COPD exacerbation? Current definitions, pitfalls, challenges and opportunities for improvement. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1801261. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01261-2018

- Steer J, Gibson J, Bourke SC. The DECAF score: predicting hospital mortality in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2012;67(11):970-976. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202103

- Ramsey SD. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, risk factors, and outcome trials: comparisons with cardiovascular disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3(7):635-640. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1513/pats.200603-094ss

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2025 report [Internet]. Milwaukee: GOLD; 2024 [cited 2025 Jan]. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/2025-gold-report/

- Reumkens C, Endres A, Simons SO, Savelkoul PHM, Sprooten RTM, Franssen FME. Application of the Rome severity classification of COPD exacerbations in a real-world cohort of hospitalised patients. ERJ Open Res. 2023;9(3):00569-2022. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00569-2022

- Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Time course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(5):1608-1613. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9908022

- Huang Q, He C, Xiong H, Shuai T, Zhang C, Zhang M, et al. DECAF score as a mortality predictor for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037923

- Memon MA, Faryal S, Brohi N, Kumar B. Role of the DECAF score in predicting in-hospital mortality in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cureus. 2019. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.4826

- Sangwan V, Chaudhry D, Malik R. Dyspnea, eosinopenia, consolidation, acidemia and atrial fibrillation score and BAP-65 score: tools for prediction of mortality in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a comparative pilot study. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2017;21:671-677. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/ijccm.ijccm_148_17

- Echevarria C, Steer J, Bourke SC. The DECAF score is a superior predictor of in-hospital death than the BAP-65 score. J Clin Respir Dis Care. 2016;2:1000111. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4172/2472-1247.1000111

- Shorr AF, Sun X, Johannes RS, Yaitanes A, Tabak YP. Validation of a novel risk score for severity of illness in acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest. 2011;140(5):1177-1183. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.10-3035

- Tabet R, Ardo C. Application of BAP-65: a new score for risk stratification in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Respir Dis Care. 2016;2(1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.4172/2472-1247.1000110

- Singanayagam A, Schembri S, Chalmers JD. Predictors of mortality in hospitalized adults with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(2):81-89. Available from: https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201208-043OC

- Terzikhan N, Verhamme KM, Hofman A, Stricker BH, Brusselle GG, Lahousse L. Prevalence and incidence of COPD in smokers and non-smokers: the Rotterdam Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31(8):785-792. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-016-0132-z

- Chung C, Lee KN, Han K, Shin DW, Lee SW. Effect of smoking on the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in young individuals: a nationwide cohort study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1190885. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1190885

- Acet-Öztürk NA, Aydin-Güçlü Ö, Yildiz MN, Demirdöğen E, Görek Dilektaşli A, Coşkun F, et al. Comparison of BAP-65, DECAF, PEARL, and MEWS scores in predicting respiratory support need in hospitalized exacerbation of chronic obstructive lung disease patients. Med Princ Pract. 2024;33(4):1-9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000538812

- Singh S, Dev A, Kumar A, Kumar S, Sinha S, Kumar Nayan S. Comparative analysis of prognostic scores for predicting mortality and the need for mechanical ventilation in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease presenting to the emergency department. Cureus. 2025;17(4):e82374. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.82374

- Oral A, Gürmen ES, Yorgancıoğlu M. The role of scoring in predicting mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eurasian J Emerg Med. 2025;24(2):106-110. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4274/eajem.galenos.2025.34712

- Memon MA, Faryal S, Brohi N, Kumar B. Role of the DECAF score in predicting in-hospital mortality in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4826. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.4826

- Shen MH, Qiu GQ, Wu XM, Dong MJ. Utility of the DECAF score for predicting survival of patients with COPD: a meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(11):4037-4050. Available from: https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202106_26045

- Echevarria C, Steer J, Heslop-Marshall K, Stenton SC, Hickey PM, Hughes R, et al. Validation of the DECAF score to predict hospital mortality in acute exacerbations of COPD. Thorax. 2016;71(2):133-140. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207775

- Weng B, Huang L, Jiao W, Wang Y, Wang M, Zhong X, et al. Development and validation of a clinical-friendly model for predicting 180-day mortality in older adults with community-acquired pneumonia. BMC Geriatr. 2025;25:271. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-025-05834-8

- Putcha N, Drummond MB, Wise RA, Hansel NN. Comorbidities and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence, influence on outcomes, and management. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;36(4):575-591. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1556063

- Divo MJ, Marin JM, Casanova C, Cabrera Lopez C, Pinto-Plata VM, Marin-Oto M, et al. Comorbidities and mortality risk in adults younger than 50 years of age with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2022;23:267. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02191-7

- Barnes P, Burney P, Silverman E, Celli BR, Vestbo J, Wedzicha JA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15076. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.76