More Information

Submitted: October 23, 2025 | Approved: November 03, 2025 | Published: November 04, 2025

How to cite this article: Glykeria C. Prognostic Factors in Pulmonary Neuroendocrine Tumors’ Treatment: A Single-center Experience. J Pulmonol Respir Res. 2025; 9(2): 053-058. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jprr.1001073

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jprr.1001073

Copyright license: © 2025 Glykeria C. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Pulmonary carcinoids; Neuroendocrine tumors; LCNEC; BPNETS; Prognostic factors; Ki-67; Pulmonary carcinoids

Prognostic Factors in Pulmonary Neuroendocrine Tumors’ Treatment: A Single-center Experience

Christou Glykeria*

Tsakalof 32, Korydallos, Athens, Greece

*Address for Correspondence: Christou Glykeria, Tsakalof 32, Korydallos, Athens, Greece, Email: [email protected]

Introduction: Lung neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are rare lung cancers classified by differentiation into well-differentiated (typical and atypical carcinoids) and poorly-differentiated forms (large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas [LCNEC] and small cell carcinomas). Carcinoid tumor management requires a multidisciplinary approach, with surgery as the main treatment.

Objectives: To identify prognostic factors and evaluate survival outcomes following surgical treatment of NETs in our institution.

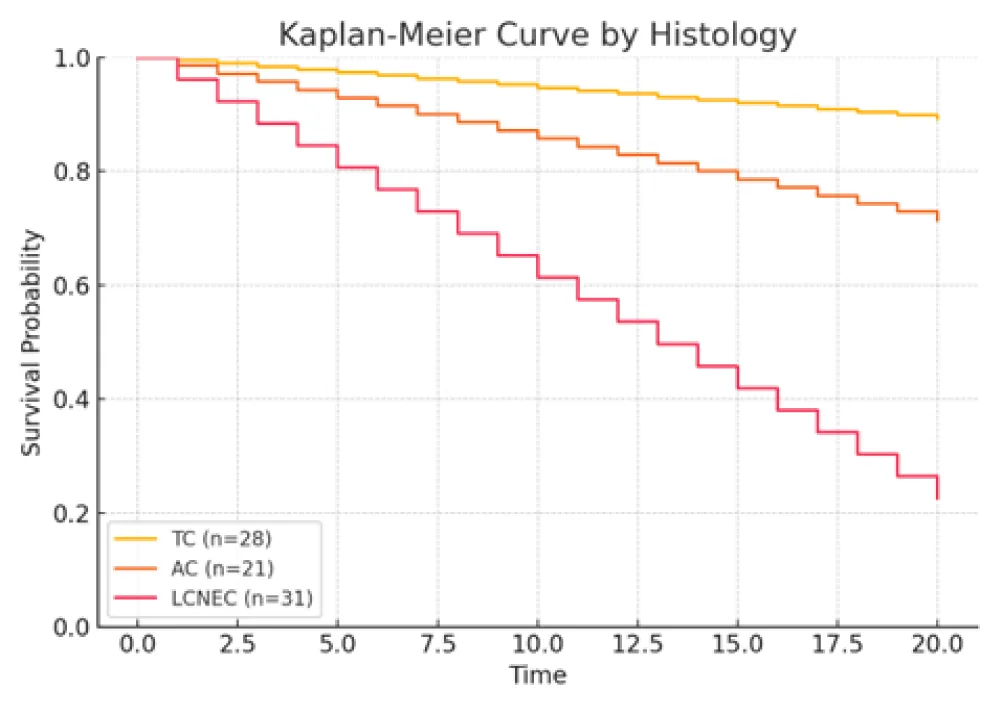

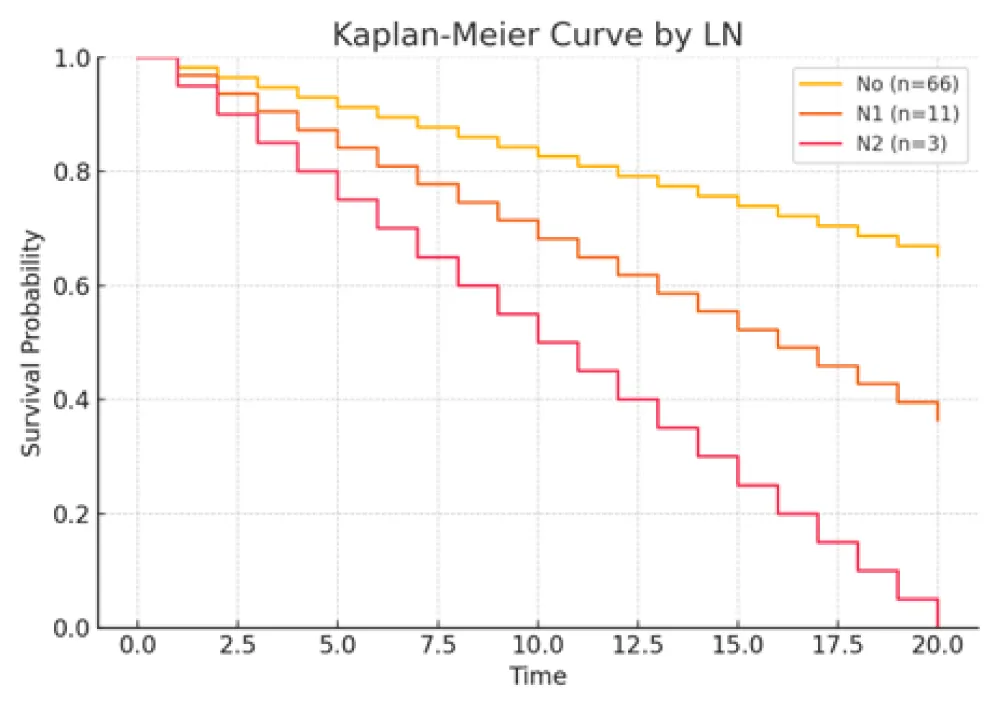

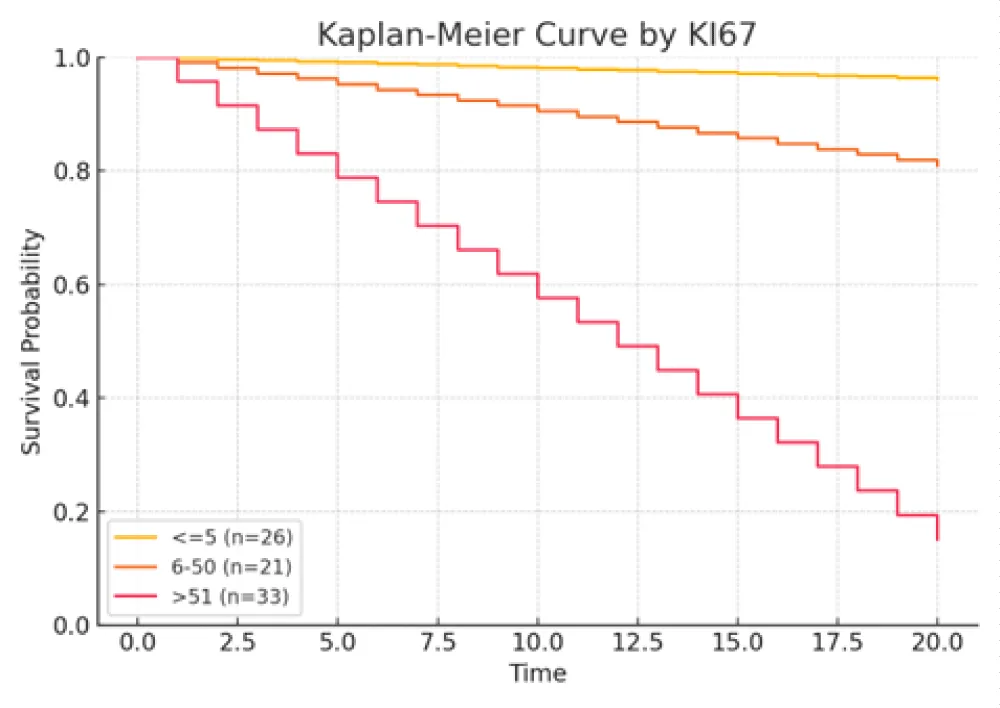

Methods: We reviewed surgical outcomes for NETs treated in our Department between January 2016 and January 2021. Survival analysis included 80 patients: 28 with typical carcinoids (TC), 21 with atypical carcinoids (AC), and 31 with LCNEC, all undergoing lobectomy, segmentectomy, pneumonectomy, or wedge resection. Variables assessed included demographics, tumor size, histology, Ki-67 index, nodal upstaging, and survival. We also compared survival by surgical type (segmentectomy vs. lobectomy) and surgical margin status. Poorly differentiated small cell carcinomas were excluded.

Results: Histological type and Ki-67 index significantly correlated with survival (p < 0.05). Tumor size and lymph node metastasis also influenced prognosis (p < 0.02). Lymph node metastases were more frequent in AC and LCNEC cases. By the last follow-up, mortality was 41.25%.

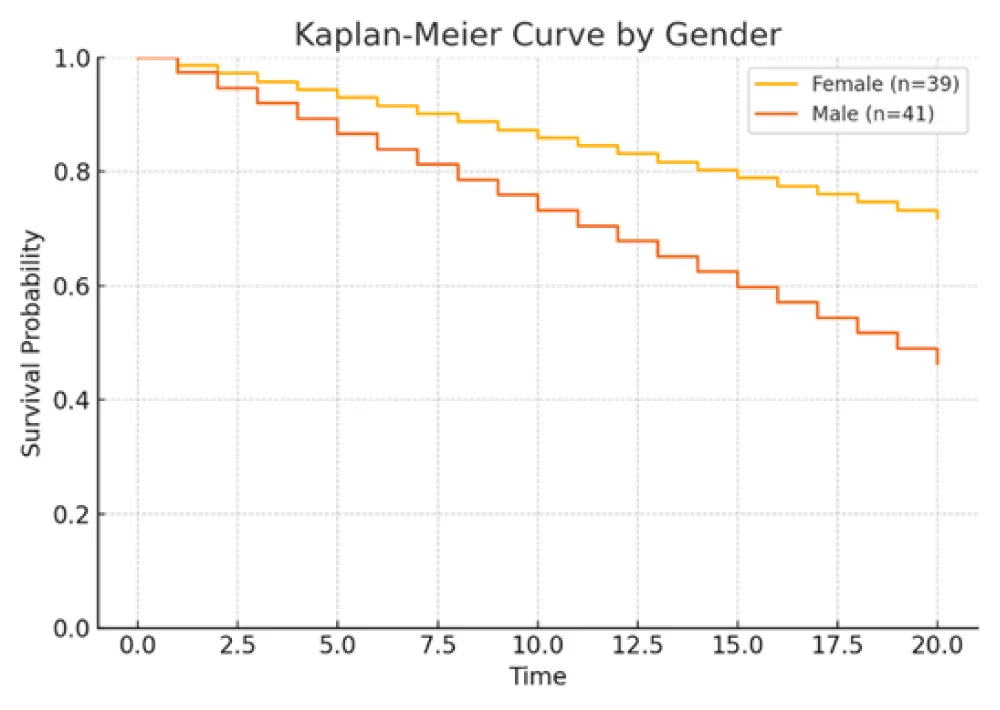

Conclusion: Surgery remains the primary treatment for TCs and ACs with localized disease, including cases with thoracic lymph node metastases. Prognosis is affected by factors such as gender, tumor subtype, cellular markers, size, and lymph node involvement.

Pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) represent a morphological spectrum of tumors, ranging from the well-differentiated typical carcinoid (TC) and the intermediate-grade atypical carcinoid (AC) to the high-grade pulmonary NETs, which include small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) and large-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) [1,2]. Pulmonary carcinoids (PCs) are slightly more prevalent in women than in men, with TCs significantly outnumbering ACs [3,4]. The incidence of PNETs has been increasing, partly due to improved diagnostic imaging and growing awareness among clinicians [5]. Surgical intervention remains the cornerstone in the management of localized PNETs, offering the best potential for curative treatment [6]. However, the optimal surgical approach, the role of adjunctive therapies, and associated outcomes remain areas of ongoing investigation [7,8].

In this context, the current study seeks to evaluate the surgical outcomes of patients diagnosed with pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) treated at our institution. By examining a cohort of patients who underwent surgical resection, this study aims to contribute to the expanding literature on prognostic indicators and identify key factors influencing overall survival [9,10]. The results indicate that prognostic factors such as the Ki-67 index, gender, lymph node involvement, histological subtype, and tumor size may significantly influence patient outcomes [2,11,12] (Figures 1-4).

Figure 1: Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival stratified by histological subtype (typical carcinoid, atypical carcinoid, and LCNEC). LCNEC patients demonstrated the poorest survival outcomes (HR > 3, 95% CI approximately 1.8–6.4, p < 0.001).

Figure 2: Kaplan–Meier curves comparing patients with and without lymph node metastasis (N0 vs. N1/N2). Presence of nodal involvement was associated with higher mortality (HR ≈ 2.6, 95% CI 1.3 - 5.4, p = 0.02).

Figure 3: Kaplan–Meier curves stratified by Ki‑67 index group (≤5%, 6% - 50%, and >51%). A higher Ki‑67 index correlated with progressively poorer survival (HR ≈ 4.1 for >51% vs. ≤5%, p < 0.001).

Figure 4: Kaplan–Meier curves comparing survival by gender. Female patients exhibited improved overall survival (HR ≈ 0.68, 95% CI 0.48–0.96, p = 0.03).

Study design and participants

Clinical and anthropometric data of the participants, including name, age, gender, smoking history, and tumor diameter, were retrieved from medical records at baseline. Tumor staging was performed using the TNM classification system [13]. A retrospective analysis was conducted to assess various clinicopathological factors, including tumor diagnosis, stage, lymph node involvement, distant metastasis, immunohistochemical molecular characteristics, and treatment strategies. Immunohistochemical markers, specifically thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) and Ki-67 index, were analyzed as representative molecular indicators [14-16]. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated as the duration from treatment initiation to either disease progression, death, or the last follow-up. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from treatment initiation to death or the last follow-up. The follow-up period concluded on January 1, 2025.

Clinicopathological characteristics were stratified based on the presence or absence of metastasis, disease progression, and mortality to identify potential risk factors for metastasis and survival outcomes [17]. The use of bronchoscopy as part of the diagnostic evaluation for all patients in this cohort provided valuable insights into the disease’s anatomical extent, facilitating targeted interventions [18,19]. This technique aids in the assessment of intrapulmonary and nodal disease, enabling clinicians to better understand the tumor’s behavior and plan surgical approaches accordingly [20].

Statistical analysis

The clinicopathological characteristics and immunophenotypes of SCLC, LCNEC, TC, and AC were compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test [21]. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables are presented as medians with ranges or interquartile ranges. Survival analyses were performed, and differences among groups were assessed for statistical significance (Table 1).

| Table 1: Patients’ characteristics. | ||||||

| Alive (n = 47) | Dead (n = 33) | |||||

| Variable | Category | n | % | n | % | p value |

| Gender | Female | 28 | 59.6 | 11 | 33.3 | 0.02 |

| Male | 19 | 40.4 | 22 | 66.7 | ||

| Histology | TC | 25 | 53.2 | 3 | 9.1 | <0.001 |

| AC | 15 | 31.9 | 6 | 18.2 | ||

| JCNEC | 7 | 14.9 | 24 | 72.7 | ||

| LN | N0 | 43 | 91.5 | 23 | 69.7 | 0.02 |

| N1 | 4 | 8.5 | 7 | 21.2 | ||

| N2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 9.1 | ||

| Ki67 | ≤50 | 22 | 51.2 | 3 | 10 | <0.001 |

| 6-50 | 16 | 37.2 | 4 | 13.3 | ||

| >50 | 5 | 11.6 | 23 | 76.7 | ||

| TTF-1 | No | 17 | 37.8 | 7 | 23.3 | 0.2 |

| Yes | 28 | 62.2 | 23 | 76.7 | ||

| Surgery | Lobectomy | 40 | 85.1 | 27 | 81.8 | |

| Segmentectomy | 4 | 8.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.16 | |

| Pneumonectomy | 1 | 2.1 | 3 | 9.1 | ||

| Wedge resection | 2 | 4.3 | 3 | 9.1 | ||

| Variable | Unit | mean | SD | mean | SD | p value |

| Age | years | 58.2 | 13.4 | 77.9 | 91.8 | 0.15 |

| Size | cm | 2.5 | 1.73 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 0.004 |

| All patients: mean age 59.4 ± 12.9 years / males: 41 (51.25%). Female (vs. Male): HR = 0.27 (95% CI 0.09-0.82, p = 0.021); Tumour size (per cm): HR = 1.35 (95% CI 1.11-1.63,. p = 0.002); LN metastasis (N1/N2 vs. N0): HR = 4.28 (95% CI 1.56-11.73, p = 0.005); Histology: AC vs.. TC: HR = 0.63 (95% CI 0.2-1.92, p = 0.415); Histology: LCNEC vs. TC: HR = 7.32 (95% CI 2.58-20.82, p = <0.001); Ki-67:. 6% - 50% vs. ≤5%: HR = 0.37 (95% CI 0.08-1.66, p = 0.196); Ki-67: >51% vs. ≤5%: HR = 5.19 (95% CI 1.98-13.61, p = <0.001). |

||||||

Univariate Cox proportional hazards analysis was performed to evaluate the prognostic significance of clinicopathological variables in patients with pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. The estimated hazard ratios (HR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p - values are presented below.

Larger tumor size, lymph node metastasis (N1/N2), higher Ki‑67 index, and LCNEC histology were each associated with increased mortality risk. Conversely, female sex correlated with improved survival. Specifically, patients with LCNEC exhibited the highest hazard of death relative to typical carcinoid (TC), while those with high Ki‑67 (>51%) also demonstrated a markedly elevated risk. These findings underscore the independent prognostic relevance of tumor differentiation, proliferative index, and nodal status.

Fisher’s exact test was conducted to validate results in cases with small subgroup counts. No statistically significant associations were observed between surgical procedure and survival (p = 0.12) or between Ki‑67 index group and survival (p = 0.08). Although trends were evident, these did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance.

The correlation between prognostic factors and survival outcomes was presented using the Kaplan–Meier curve [22] (Figures 1-4). A p - value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Clinical and pathological characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the 80 patients are detailed in Table 2. The study population included a slightly higher proportion of males (51.3%). LCNEC was the most commonly observed subtype (38.8%), followed by TC (35.0%) and AC (26.2%), consistent with prior reports indicating the aggressive nature and rising incidence of LCNEC [23,24]. LCNEC cases frequently exhibited higher proliferative activity, while TC and AC subtypes were associated with lower Ki-67 indices [2,25].

| Table 2: Baseline patients’ characteristics. | |||

| All patients (n = 80) | |||

| Variable | Category | n | % |

| Gender | Male | 41 | 51.3 |

| TC | 28 | 35.0 | |

| Histology | AC | 21 | 26.2 |

| JCNEC | 31 | 38.8 | |

| LN | N0 | 66 | 82.4 |

| N1 | 11 | 13.8 | |

| N2 | 3 | 3.8 | |

| Ki67 | ≤5 | 25 | 31.2 |

| 6-50 | 20 | 25.0 | |

| >50 | 28 | 35.0 | |

| not available | 7 | 8.8 | |

| TTF-1 | No | 24 | 30.0 |

| Yes | 51 | 63.7 | |

| not available | 5 | 6.3 | |

| Surgery | Lobectomy | 67 | 83.7 |

| Segmentectomy | 4 | 5.0 | |

| Pneumonectomy | 4 | 5.0 | |

| Wedge resection | 5 | 6.3 | |

| Mortality | Alive | 47 | 58.7 |

| Dead | 33 | 41.3 | |

Most patients (82.4%) had no lymph node (LN) metastasis at presentation. Nodal involvement (N1 or N2) was more prevalent in patients with LCNEC, suggesting a more aggressive disease phenotype [3,26]. Ki-67 index was ≤5% in 31.2% of patients, between 6% - 50% in 25.0%, and >51% in 35.0%, with 8.8% missing data. High Ki-67 levels were predominantly found in LCNEC cases, whereas lower levels were characteristic of carcinoid tumors [2,27,28]. TTF-1 was expressed in 63.7% of the cohort, absent in 30.0%, and unavailable in 6.3%. TTF-1 positivity was more common in LCNEC, with lower expression in TC and AC tumors [29,30].

Lobectomy was the predominant surgical intervention (83.7%), while segmentectomy, pneumonectomy, and wedge resection were less frequently performed and typically reserved for patients with less aggressive tumors or limited surgical fitness [31]. At the time of follow-up, 41.3% of patients had died. Mortality was higher among patients with LCNEC, nodal metastasis, and elevated Ki-67 indices, whereas better survival was observed in patients with TC histology, no LN involvement, and low Ki-67 index [11,12,32].

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective single-center design and limited cohort size may restrict the generalisability of the findings. Second, as a univariate analysis, it does not fully adjust for potential confounding factors. Third, histopathological and Ki‑67 assessments were performed within a single institution, potentially introducing observer bias. Finally, variation in follow‑up duration among patients may have influenced survival outcomes. Future multicentre prospective studies are recommended to validate these observations and to explore additional prognostic biomarkers.

Survival risk factors’ analysis of PNETs

Survival outcomes were significantly associated with gender (Female 59.6% vs Male 40.4%, p = 0.02), tumor size (deceased: 3.9 cm vs. alive: 2.5 cm, p = 0.004), lymph-node metastasis (p = 0.02), and Ki-67 index (>51% in 76.7% of deceased vs. 11.6% of alive; p < 0.001) [11,33,34] (Table 1. Patients’5 characteristics). Histological subtype was also a major prognostic factor: LCNEC was more frequent in deaths (72.7%) compared to TC (9.1%) (p = 0.001). Independent prognostic indicators for survival included lymph-node status, histological type, gender, Ki-67 index, and tumor size [2,12,28,35]. Kaplan–Meier plots illustrated that female patients had higher survival rates, while LCNEC patients had significantly poorer outcomes. Patients with low Ki-67 index (≤5%) demonstrated the highest survival, reinforcing Ki-67’s prognostic utility [25,34,36].

Pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs), comprising approximately 30% of all neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and 20% of lung cancers, have exhibited increasing incidence over recent decades, a trend partially attributed to histopathological reclassification and improved diagnostic awareness [1,2,5,17]. Despite this, PNETs remain poorly characterized at both the etiopathological and molecular levels [1,2,6]. While most are sporadic, around 10% are associated with hereditary syndromes such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) [19].

Histologically, PNETs are categorized into four distinct subtypes: typical carcinoids (TCs), atypical carcinoids (ACs), large-cell neuroendocrine carcinomas (LCNECs), and small-cell lung carcinomas (SCLCs), each differing in clinical behavior and prognosis [2,25,37]. TCs generally behave indolently with a favorable 5-year survival (~90%), while ACs show intermediate aggressiveness and poorer outcomes (5-year survival: 50% - 80%) [20,21]. LCNECs and SCLCs exhibit highly aggressive courses, early metastasis, and low survival rates (LCNEC: 15% - 57%; SCLC: <5%) [23,26,30,38,39].

The Ki-67 index is increasingly recognized as a critical biomarker in PNETs [40]. Elevated Ki-67 values (>5% in TC, >10% overall) are associated with greater tumor aggressiveness and worse outcomes, providing predictive and prognostic utility beyond mitotic count alone [28,41-47]. In this study, a Ki-67 index >51% was strongly associated with mortality (p < 0.001), underscoring its importance in risk stratification. Ki-67 also helps differentiate between carcinoid and high-grade tumors and may assist in refining classifications in borderline cases [46,48,49].

Lymph node metastasis emerged as a statistically significant adverse prognostic factor (p = 0.02), corroborating prior studies showing a strong association between nodal involvement and reduced survival [3,4,11,31]. AC and LCNEC subtypes demonstrated higher rates of lymphatic spread compared to TCs, reflecting their aggressive biology [26,34,50].

In our retrospective cohort, key risk factors for poor overall survival included male gender, older age, larger tumor size, lymph node metastasis, poorly differentiated histological subtypes, and high Ki-67 index [11,33,34]. These findings are in alignment with existing literature [29,32,35]. Importantly, our results support the growing consensus that surgery, particularly when combined with chemotherapy or radiotherapy in selected cases, can significantly improve survival outcomes, especially in early-stage or localized disease [6,16,27,31,51].

Moreover, the utility of immunohistochemical markers such as TTF-1 and Ki-67 was reaffirmed. TTF-1 expression was more commonly observed in LCNEC and SCLC, consistent with their neuroendocrine and pulmonary origins [14,29,30]. In contrast, TC and AC subtypes demonstrated weaker or absent expression, reinforcing their diagnostic value in tumor subtyping [32,52].

In conclusion, this study highlights the prognostic significance of histological classification, Ki-67 index, tumor size, and lymph node status in patients with pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs). Our findings demonstrate that high-grade tumors (e.g., LCNEC), elevated Ki-67 indices, nodal metastasis, and larger tumor size are significantly associated with poorer survival outcomes [2,3,25,34]. These variables should be routinely integrated into diagnostic and treatment planning workflows.

The incorporation of immunohistological markers such as Ki-67 and TTF-1 into clinical protocols may enhance prognostication and guide treatment selection [14,29,48,52]. As the clinical understanding of PNETs evolves, personalized surgical strategies and long-term follow-up based on tumor biology and patient-specific factors will be essential for improving clinical outcomes [1,20,53].

Further multicenter studies with larger cohorts are warranted to validate these findings and uncover additional prognostic biomarkers or molecular targets for therapy [2,5,28,54]. The integration of molecular pathology with clinical staging offers a promising path toward more effective and individualized management of PNETs.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

- Modlin IM, Kidd M, Filosso PL, Roffinella M, Lewczuk A, Cwikla J, et al. Molecular strategies in the management of bronchopulmonary and thymic neuroendocrine neoplasms. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(Suppl 15):S1458-S1473. Available from: https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2017.03.82

- Rekhtman N. Lung neuroendocrine neoplasms: recent progress and persistent challenges. Mod Pathol. 2022;35(Suppl 1):36-50. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-021-00943-2

- Zhang S, Chen J, Zhang R, Xu L, Wang Y, Yuan Z, et al. Pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors: study of 266 cases focusing on clinicopathological characteristics, immunophenotype, and prognosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(3):1063-1077. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-022-03970-x

- Yang H, Liu T, Li M, Fang Z, Luo L. Does examined lymph node count influence survival in surgically resected early-stage pulmonary typical carcinoid tumors? Am J Clin Oncol. 2022;45(12):506-513. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/coc.0000000000000958

- Feola T, Centello R, Sesti F, Puliani G, Verrico M, Di Vito V, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinomas with atypical proliferation index and clinical behavior: a systematic review. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(6):1247. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13061247

- Rosai J, Higa E. Mediastinal endocrine neoplasm, of probable thymic origin, related to carcinoid tumor. Clinicopathologic study of 8 cases. Cancer. 1972;29:1061-1074. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(197204)29:4%3C1061::aid-cncr2820290456%3E3.0.co;2-3

- Goldman A, Conner CL. Benign tumors of the lungs with special reference to adenomatous bronchial tumors. Dis Chest. 1950;17(6):644-680. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.17.6.644

- Bensch KG, Corrin B, Pariente R, Spencer H. Oat-cell carcinoma of the lung: its origin and relationship to bronchial carcinoid. Cancer. 1968;22(6):1163-1172. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(196811)22:6%3C1163::aid-cncr2820220612%3E3.0.co;2-l

- Arrigoni MG, Woolner LB, Bernatz PE. Atypical carcinoid tumors of the lung. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1972;64(3):413-421. PMID: 5054879. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5054879/

- Mills SE, Cooper PH, Walker AN, Kron IL. Atypical carcinoid tumor of the lung: a clinicopathologic study of 17 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6(7):643-654. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-198210000-00006

- DeLellis RA, Dayal Y, Wolfe HJ. Carcinoid tumors. Changing concepts and new perspectives. Am J Surg Pathol. 1984;8(4):295-300. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6369998/

- Klöppel G. Oberndorfer and his successors: from carcinoid to neuroendocrine carcinoma. Endocr Pathol. 2007;18(3):141-144. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-007-0021-9

- Bernatz PE, Harrison EG, Clagett OT. Thymoma: a clinicopathologic study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1961;42:424-444. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13868094/

- Lausi PO, Refai M, Filosso PL, Ruffini E, Oliaro A, Guerrera F, Brunelli A. Thymic neuroendocrine tumors. Thorac Surg Clin. 2014;24(3):327-332. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thorsurg.2014.05.007

- Rosai J, Higa E, Davie J. Mediastinal endocrine neoplasm in patients with multiple endocrine adenomatosis. A previously unrecognized association. Cancer. 1972;29(4):1075-1083. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(197204)29:4%3C1075::aid-cncr2820290457%3E3.0.co;2-o

- Filosso PL, Yao X, Ahmad U, Zhan Y, Huang J, Ruffini E, et al. Outcome of primary neuroendocrine tumors of the thymus: a joint analysis of the International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons databases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149(1):103-109.e2. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.08.061

- Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, et al. One hundred years after "carcinoid": epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(18):3063-3072. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.15.4377

- Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, Chan A, Malfertheiner MV, Modlin IM. Bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 2008;113(1):5-21. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23542

- de Laat JM, Pieterman CR, van den Broek MF, Twisk JW, Hermus AR, Dekkers OM, et al. Natural course and survival of neuroendocrine tumors of the thymus and lung in MEN1 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(9):3325-3333. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2014-1560

- Caplin ME, Baudin E, Ferolla P, Filosso P, Garcia-Yuste M, Lim E, et al. Pulmonary neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors: European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society expert consensus and recommendations for best practice for typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(8):1604-1620. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv041

- Jeung MY, Gasser B, Gangi A, Charneau D, Ducroq X, Kessler R, et al. Bronchial carcinoid tumors of the thorax: spectrum of radiologic findings. Radiographics. 2002;22(2):351-365. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.22.2.g02mr01351

- Oberg K, Hellman P, Kwekkeboom D, Jelic S; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Neuroendocrine bronchial and thymic tumors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21 Suppl 5:v220-222. Erratum in: Ann Oncol. 2011;22(1):242-243. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdq191

- Phan AT, Oberg K, Choi J, Harrison LH Jr, Hassan MM, Strosberg JR, et al. NANETS consensus guideline for the diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the thorax (includes lung and thymus). Pancreas. 2010;39(6):784-798. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/mpa.0b013e3181eb7451

- Rosado de Christenson ML, Abbott GF, Kirejczyk WM, Galvin JR, Travis WD. Thoracic carcinoids: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19(3):707-736. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.19.3.g99ma11707

- WHO Classification of Tumors Editorial Board. Thoracic Tumors. 5th ed. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2021. Available from: https://publications.iarc.who.int/Book-And-Report-Series/Who-Classification-Of-Tumours/Thoracic-Tumours-2021

- Rekhtman N. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134(11):1628-1638. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5858/2009-0583-rar.1

- Clinical Lung Cancer Genome Project (CLCGP); Network Genomic Medicine (NGM). A genomics-based classification of human lung tumors. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(209):209ra153. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3006802

- Cree IA, Tan PH, Travis WD, et al. Counting mitoses: SI(ze) matters. Mod Pathol. 2021;34:1651-1657. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-021-00825-7

- Riihimäki M, Hemminki A, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. The epidemiology of metastases in neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(12):2679-2686. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30400

- Rekhtman N, Desmeules P, Litvak AM, Pietanza MC, Santos-Zabala ML, Ni A, et al. Stage IV lung carcinoids: spectrum and evolution of proliferation rate, focusing on variants with elevated proliferation indices. Mod Pathol. 2019;32(8):1106-1122. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0248-2

- Hermans BCM, de Vos-Geelen J, Derks JL, Latten L, Liem IH, van der Zwan JM, et al. Unique metastatic patterns in neuroendocrine neoplasms of different primary origin. Neuroendocrinology. 2021;111(11):1111-1120. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1159/000513249

- Yatabe Y, Dacic S, Borczuk AC, Warth A, Russell PA, Lantuejoul S, et al. Best practices recommendations for diagnostic immunohistochemistry in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(3):377-407. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2018.12.005

- Rooper LM, Sharma R, Li QK, Illei PB, Westra WH. INSM1 demonstrates superior performance to the individual and combined use of synaptophysin, chromogranin, and CD56 for diagnosing neuroendocrine tumors of the thoracic cavity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(11):1561-1569. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/pas.0000000000000916

- Mukhopadhyay S, Dermawan JK, Lanigan CP, Farver CF. Insulinoma-associated protein 1 (INSM1) is a sensitive and highly specific marker of neuroendocrine differentiation in primary lung neoplasms: an immunohistochemical study of 345 cases, including 292 whole-tissue sections. Mod Pathol. 2019;32(1):100-109. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0122-7

- Sakakibara R, Kobayashi M, Takahashi N, Inamura K, Ninomiya H, Wakejima R, et al. Insulinoma-associated protein 1 (INSM1) is a better marker for the diagnosis and prognosis estimation of small cell lung carcinoma than neuroendocrine phenotype markers such as chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and CD56. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44(6):757-764. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0122-7

- Yoshida A, Makise N, Wakai S, Kawai A, Hiraoka N. INSM1 expression and its diagnostic significance in extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2018;31(5):744-752. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.189

- Rindi G, Klimstra DS, Abedi-Ardekani B, Asa SL, Bosman FT, Brambilla E, et al. A common classification framework for neuroendocrine neoplasms: an International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and World Health Organization (WHO) expert consensus proposal. Mod Pathol. 2018;31(12):1770-1786. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0110-y

- Rekhtman N, Pietanza MC, Hellmann MD, Naidoo J, Arora A, Won H, et al. Next-generation sequencing of pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma reveals small cell carcinoma-like and non-small cell carcinoma-like subsets. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(14):3618-3629. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-15-2946

- Quinn AM, Chaturvedi A, Nonaka D. High-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung with carcinoid morphology: a study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(2):263-270. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/pas.0000000000000767

- Tsai HK, Hornick JL, Vivero M. INSM1 expression in a subset of thoracic malignancies and small round cell tumors: rare potential pitfalls for small cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2020;33(8):1571-1580. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-0517-0

- Warmke LM, Tinkham EG, Ingram DR, Lazar AJ, Panse G, Wang WL. INSM1 expression in angiosarcoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;155(4):575-580. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqaa168

- Pelosi G, Massa F, Gatti G, Righi L, Volante M, Birocco N, et al. Ki-67 evaluation for clinical decision in metastatic lung carcinoids: a proof of concept. Clin Pathol. 2019;12:2632010X19829259. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/2632010x19829259

- Marchiò C, Gatti G, Massa F, Bertero L, Filosso P, Pelosi G, et al. Distinctive pathological and clinical features of lung carcinoids with high proliferation index. Virchows Arch. 2017;471(6):713-720. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-017-2177-0

- Zahel T, Krysa S, Herpel E, Stenzinger A, Goeppert B, Schirmacher P, et al. Phenotyping of pulmonary carcinoids and a Ki-67-based grading approach. Virchows Arch. 2012;460(3):299-308. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-012-1194-2

- Pelosi G, Rindi G, Travis WD, Papotti M. Ki-67 antigen in lung neuroendocrine tumors: unraveling a role in clinical practice. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9(3):273-284. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/jto.0000000000000092

- Marchevsky AM, Hendifar A, Walts AE. The use of Ki-67 labeling index to grade pulmonary well-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasms: current best evidence. Mod Pathol. 2018;31(10):1523-1531. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0076-9

- de Vilhena AF, das Neves Pereira JC, Parra ER, Balancin ML, Ab Saber A, Martins V, et al. Histomorphometric evaluation of the Ki-67 proliferation rate and CD34 microvascular and D2-40 lymphovascular densities drives the pulmonary typical carcinoid outcome. Hum Pathol. 2018;81:201-210. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2018.07.007

- Dermawan JKT, Farver CF. The role of histologic grading and Ki-67 index in predicting outcomes in pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44(2):224-231. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/pas.0000000000001358

- Clay V, Papaxoinis G, Sanderson B, Valle JW, Howell M, Lamarca A, et al. Evaluation of diagnostic and prognostic significance of Ki-67 index in pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Clin Transl Oncol. 2017;19(5):579-586. Epub 2016 Nov 15. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-016-1568-z

- Hermans BCM, Derks JL, Moonen L, Habraken CHJ, der Thüsen JV, Hillen LM, et al. Pulmonary neuroendocrine neoplasms with well-differentiated morphology and high proliferative activity: illustrated by a case series and review of the literature. Lung Cancer. 2020;150:152-158. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.10.015

- Singh S, Bergsland EK, Card CM, Hope TA, Kunz PL, Laidley DT, et al. Commonwealth Neuroendocrine Tumour Research Collaboration and the North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with lung neuroendocrine tumors: an international collaborative endorsement and update of the 2015 European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society expert consensus guidelines. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(10):1577-1598. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2020.06.021

- Uccella S, La Rosa S, Volante M, Papotti M. Immunohistochemical biomarkers of gastrointestinal, pancreatic, pulmonary, and thymic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 2018;29(2):150-168. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-018-9522-y

- Caplin ME, Baudin E, Ferolla P, Filosso P, Garcia-Yuste M, Lim E, et al. Pulmonary neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumors: European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society expert consensus and recommendations for best practice for typical and atypical pulmonary carcinoids. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(8):1604-1620. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv041

- Alcala N, Leblay N, Gabriel AAG, Mangiante L, Hervas D, Giffon T, et al. Integrative and comparative genomic analyses identify clinically relevant pulmonary carcinoid groups and unveil the supra-carcinoids. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3407. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11276-9