More Information

Submitted: June 07, 2021 | Approved: October 04, 2021 | Published: October 05, 2021

How to cite this article: Singh D, Kaur H, Kajal NC. COVID-19 and rhino-orbital mucormycosis – a case report. J Pulmonol Respir Res. 2021; 5: 094-096.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jprr.1001032

Copyright License: © 2021 Singh D, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: COVID-19; Diabetes Mellitus (DM); Mucormycosis; Amphotericin B

COVID-19 and rhino-orbital mucormycosis – a case report

Dilbag Singh1*, Harveen Kaur1 and NC Kajal2

1Junior Resident, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Government Medical College, Amritsar, Punjab, India

2Professor, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Government Medical College, Amritsar, Punjab, India

*Address for Correspondence: Dilbag Singh, Junior Resident, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Government Medical College, Amritsar, Punjab, India, Email: [email protected]

There is a constant rise in cases of rhino-orbital mucormycosis in people with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Generally, Mucormycosis develops in immunosuppression or debilitating diseases. In cases having head and neck involvement, the mold enters the respiratory tract with further involvement of nose and sinuses and there is consecutive progression into orbital and intracranial structures. Diabetes Mellitus (DM) is an independent risk factor for both severe COVID-19 and mucormycosis. The clinical examination and direct smears are helpful for early diagnosis of the disease and timely intervention. For the better prevention and management of such opportunistic infections in COVID-19 patients, it is prudent to establish prophylactic treatment protocols along with rational use of corticosteroids. We here report a case of Rhino-orbital Mucormycosis infection caused by Rhizopus oryzae in a COVID-19 patient with Diabetes Mellitus.

There has been a rapid spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) globally [1]. In influenza, SARS, MERS, and other viral respiratory illnesses secondary infections are a well-described occurrence. But in COVID-19 pneumonia, super-infections and co-infections are under exploration [2].

In severely ill, hospitalized COVID-19 patients, secondary infections are reportedly common, encompassing between 10% and 30% of cases, fungal being 10 times more common [2]. Earlier, both Aspergillus and Candida have been reported as the main fungal pathogens for co-infection in such cases. Recently, there has been reported a rise in cases of mucormycosis in people with COVID-19 worldwide.

The main facilitating factor in such cases is that Mucorales spores need an ideal environment of low oxygen (hypoxia), high glucose (diabetes, steroid-induced hyperglycemia), acidic medium, high iron levels and decreased phagocytic activity of WBC’s due to immunosuppression coupled with other risk factors like prolonged hospitalization with or without mechanical ventilators.

The side effects of corticosteroids (i.e., Methylprednisolone and Dexamethasone) used to modulate the inflammation mediated lung injury and to reduce the progression of respiratory failure in COVID-19, include increased secondary infections, manifestation of latent diabetes mellitus, weight gain, dizziness, insomnia and muscle weakness [3]. While corticosteroids use for long periods has often been associated with several opportunistic fungal infections, even a short course of corticosteroids has recently reported to link with mucormycosis especially in people with DM.

Mucormycosis, caused by Mucorales species of the phylum Zygomycota is a potentially lethal infection that occurs most commonly in immunocompromised hosts, particularly in those with diabetes mellitus, malignancies like leukemia and lymphoma [4]. The Rhizopus Oryzae is most common type and responsible for majority of cases in humans.

The global incidence of mucormycosis ranges from 0.005 to 1.7 per million population. In Indian population the prevalence is about 80 times higher than developed nations (0.14 per 1000) [5]. The global fatality rate of mucormycosis is 46%. However, it can be as high as 50% to 80% when there is intracranial or orbital involvement, irreversible immune suppression [6]. The rapidity of dissemination of mucormycosis is an extraordinary phenomenon and even a 12-hour delay in the diagnosis could be fatal. Thus, in immunocompromised patients a high suspicion for this disease should be considered. Tissue necrosis, although the hallmark of mucormycosis is often a late sign.

Due to the difficulty in diagnosis, mucormycosis adds onto the poor prognosis in such immune suppressed COVID-19 patients. Thus, it needs an early diagnosis to initiate the essential treatment. Delay of a week can double the 30-day mortality from 35% to 66%. The overall prognosis of the disease remains poor despite the early aggressive combined surgical and medical therapy [7].

A 60-year-old male came with history of high-grade fever, body aches, dry cough for 6 days. Detailed history was obtained from the patient. He was a known case of type 2 Diabetes mellitus, on medications from past 1 year. There was no previous history of any other chronic illness and no history of any substance abuse.

Baseline investigations were performed. Total leukocyte count 15,300, Fasting blood sugar (FBS) 191 mg/dL, Post-prandial blood sugar (PPBS) 286 mg/dL, HbA1c 9.5%, S. Cholesterol 188.7 mg%, S. Triglycerides 198.9 mg%, Serum Interleukin-6 39.2 pg/mL, CRP 19.45 mg/l, D-Dimer 480 ng/mL. Nasopharyngeal swab sent for RT-PCR tested positive for COVID-19.

He was managed for COVID-19 as per the existing treatment protocol. After 10 days, he developed swelling and pain in the right eye along with right sided headache. On clinical examination, there was soft peri-orbital swelling with discoloration, proptosis and chemosis of the right eyeball. Nasal crusting along with nasal obstruction on right side.

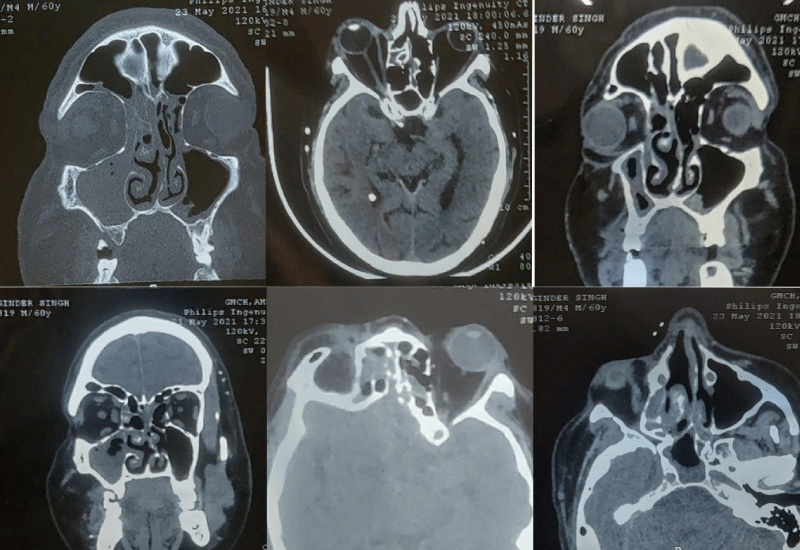

NCCT of Paranasal Sinuses (PNS) was done, which revealed features suggestive of fungal sinusitis- circumferential mucosal thickening with interspersed hyperdensities in bilateral paranasal sinuses (right> left) with bulky right medial rectus muscle and retrobulbar streakiness along with proptosis of right globe and inferior turbinate hypertrophy.

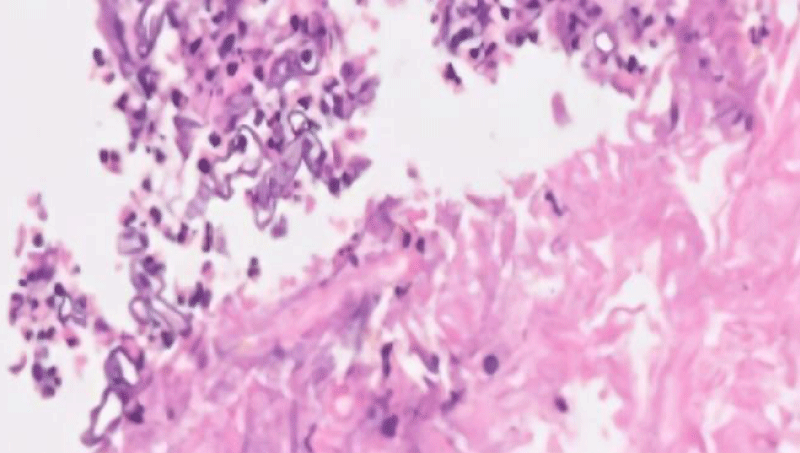

FESS was done and sinuses were debrided. Specimens were sent for culture sensitivity and histopathology. On histopathological analysis, there were present broad-based hyphae and gram-positive bacilli along with areas of necrosis, hence raising the suspicion of mucormycosis. The microbiological examination revealed the growth of Rhizopus oryzae and special stains for fungal hyphae (PAS and GMS) were positive. The medical regimen was started with I.V. Amphotericin B, followed by surgical debridement for removal of necrotic tissue.

On serial follow-up, there was gradual improvement in the eye movements of right eye, compared with the normal along with resolution of chemosis (Figures 1-3).

Figure 1: Preoperative photograph showing peri-orbital swelling with discolouration, proptosis and chemosis of right eye.

Figure 2: NCCT PNS image showing the extension of the lesion.

Figure 3: Histopathology of the specimen showed broad-based aseptate fungal hyphae suggestive of mucormycosis.

Mucormycosis can involve nose, sinuses, orbit, central nervous system (CNS), lung (pulmonary), gastrointestinal tract (GIT), skin, jaw bones, joints, heart, kidney, and mediastinum (invasive type). Mucormycosis of head and neck region comprises isolated nasal, rhino-orbital or rhino-orbital-cerebral forms. Majority of the clinical isolates belong to genus Rhizopus and are frequently observed in association with uncontrolled diabetes and DKA.

These saprophytic, ubiquitous fungi are potent in the temperate climates. The contributing risk factors for development of disease include diabetes mellitus, leukemias, immunosuppressive therapies, neutropenias, iron-overload, HIV/AIDS. The causative agent enters the host through the respiratory tract and grows along the internal elastic lamina of arteries, with resultant thrombosis and infarction [8]. The disease progression from nose and sinuses can be direct or through vascular occlusion. Invasion through superior orbital fissure, ophthalmic vessels, cribriform plate, carotid artery or perineural route can result in intracranial involvement [9].

Classically, diagnosis is dependent on clinical presentation, pathological findings and imaging. Although for the primary management of the disease, we need to correct the underlying cause that cannot be achieved in COVID-19 patients who are dependent on high-dose steroid therapy. The mainstay of management is medical treatment with Amphotericin B and surgical debridement. Once the diagnosis is confimed, conservative management is to be initiated for the patient.

Although prognosis is dependent on multiple factors, early treatment initiation remains the mainstay.

The ongoing rise in mucormycosis cases is due to trinity of diabetes, rampant use of corticosteroid and COVID-19 (cytokine storm, lymphopenia, endothelial damage). In COVID-19 patients, opportunistic infections can significantly add to the mortality and morbidity, thus need prevention and early management. Prophylactic treatment protocols along with rationale use of corticosteroids play a significant role towards a better prognosis.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

- Jayaweera M, Perera H, Gunawardana B, Manatunge J. Transmission of COVID-19 virus by droplets and aerosols: a critical review on the unresolved dichotomy. Environ Res. 2020; 188: 109819. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32569870/

- Superinfections and coinfections in COVID-19. MedPage Today. https://www.medpagetoday.com/infectiousdisease/covid19/86192

- Methylprednisolone for patients with COVID-19 severe acute respiratory syndrome. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04323592

- Talmi YP, Goldschmied-Reouven A, Bakon M, Barshack I, Wolf M, et al. Rhino-orbital and rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002; 127: 22-31. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12161726/

- Chander J, Kaur M, Singla N, Punia R, Singhal S, Attri A, et al. Mucormycosis: battle with the deadly enemy over a five-year period in India. J Fungi. 4: 46. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29642408/

- Deutsch PG, Whittaker J, Prasad S. Invasive and non-invasive fungal rhinosinusitis—a review and update of the evidence. Medicina. 2019; 55: 1-14. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31261788/

- Werthman-Ehrenreich A. Mucormycosis with orbital compartment syndrome in a patient with COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2021; 42: 264. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32972795/

- Gupta S, Goyal R, Kaore NM. Rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis: battle with the deadly enemy. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020; 72: 104-111. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32158665/

- Parsi K, Itgampalli RK, Vittal R, Kumar A. Perineural spread of rhino-orbitocerebral mucormycosis caused by Apophysomyces elegans. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2013; 16: 414-417. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24101833/